Introducing Open Source Intelligence to the Police

… Little did the police officers’ trainees know that the seemingly “harmless” tweet at the beginning of my seminar features a high-value organised-crime asset, sitting comfortably in their own backyard.

I don’t tell them that at first. I just project the tweet and say nothing.

For a few seconds, the room glances and registers the details in a regular social-media-scrolling fashion: a nice bar, two guys, the one who tweeted has his identity blurred, the other one seems to be called Daniel, a boxing emoji… and their attention starts to drift.

Only those with a natural investigative flair dig deeper. They notice the time and date caption - “14:38 - February 11, 2021” - the location “Dubai, United Arab Emirates”, and then they start wondering why I chose to open a seminar on criminal investigations with this particular tweet.

The fact that I blurred the author’s identity suggests that I ethically need to keep him out of the discussion. The other individual, Daniel, becomes the person of interest.

The most astute of my trainees are triggered by the combination of the luxurious room in the background and the boxing emoji. Their instinct is shaped by a quiet reality that policing has been catching up with for years: Modern sport is an attractive nest for organised and white-collar crime.

A Real Threat to Professional Sports

That might sound dramatic. But when you look at sport as an economic sector, it makes uncomfortable sense:

huge cash and betting flows + light regulation + enormous social prestige.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime's recent Game Over report puts it bluntly: organised criminal groups have a long history of infiltrating sports and exploiting them systematically for illegal betting, money laundering and whitewashing. While football remains the primary target worldwide, the report notes that criminal activity is also increasing in other sports - particularly boxing.

The historic weak spot: Boxing

If you had to design a sport that is structurally vulnerable to organised crime, you would end up very close to professional boxing: two fighters, a small circle of managers and promoters, big cash and very little transparency. By the mid-1980s, the New Jersey State Commission of Investigation was already publishing Organised Crime in Boxing, exposing the intrusion of mob figures as managers and promoters concealed behind front companies - skimming purses and manipulating championships.

So when my trainees see “money + boxing” in that tweet, they are unconsciously connecting it to boxing as a historical crime scene for organised crime, and to sport in general as a low-risk, high-reward infrastructure for laundering and influence.

This opens the door for me to zoom in on a modern example and reveal to the trainees who “Daniel” is according to open sources.

Daniel

The man smiling in the tweet is Daniel Kinahan, an Irish boxing adviser and suspected crime boss.

On the sports side of his life, his public image is almost admirable. He is described as a “global power broker” and a man who can make impossible fights happen. He co-founded MTK Global (originally Macklin’s Gym Marbella) with former boxer Matthew Macklin, building it into a management company that represented numerous fighters, including world champions like Tyson Fury and Billy Joe Saunders. Senior promoters and broadcasters have publicly praised his role as a deal-maker. In 2020, Tyson Fury thanked him in a video-recorded message for “getting this deal over the line” when a two-fight agreement with Anthony Joshua was announced.

Underneath this apparent success as a sports businessman, lies a deep and sombre layer according to Irish journalists and Western law-enforcement communities. In 2018, Ireland’s High Court accepted evidence from the Criminal Assets Bureau that he controlled and managed the Kinahan organised crime group, involved in large-scale drug trafficking and weapons smuggling. In April 2022, the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned Daniel, his father “Christy” and his brother Christopher Jr. as leaders of the Kinahan Organised Crime Group, describing it as a significant transnational cocaine-trafficking and money-laundering organisation, and offering multi-million-dollar rewards for information leading to their disruption. Recent long-form reporting, including by The New Yorker and the ICIJ, places the Kinahans within a so-called “super cartel” supplying a substantial share of Europe’s cocaine market.

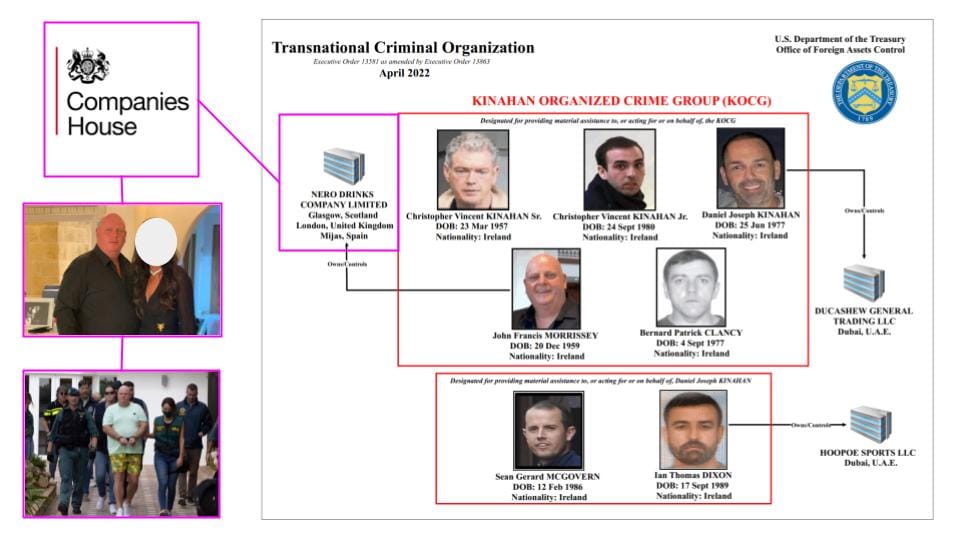

The Cartel’s Organisational Chart

According to the U.S. Treasury organizational chart of the Kinahans, Christopher Senior and his two sons, Daniel and Christopher Junior, sit at the top of the organization. Four identified associates and three companies branch underneath them. For open-source investigators, that diagram is a treasure: it provides not only the names, dates of birth, and nationalities of “persons of interests” but also the names and jurisdictions of the corporate structures that can be chased through public records.

It’s my bridge to shift their attention from investigating humans to investigating organisations. We zoom in on one particular firm: Nero Drinks Company Ltd.

We look it up together on the UK business registry, the trainees find a Scottish private company of that name, and one person immediately stands out: someone sharing the family name of John Francis Morrissey, one of the associates on the chart. The registered director is reported to be Morrissey’s wife. That is basic Open Source Investigation (OSINT) in action: in two simple steps, they connect a glossy vodka brand, a sanctioned money-laundering suspect and the spouse who appears as the official director.

More than a Classroom Exercise

That “harmless” tweet is more than a classroom exercise. Cases like this influence a country’s safety reputation, a city’s investment appeal, and the public’s trust in international sports federations they follow so closely.

When alleged organised-crime figures find shelter in elite sport, the risk is not only a fixed match; it is irreversible investment damage, exposure to sanctions, and the real possibility that violence and corruption have found a protected channel for revenue.

For regulators and businesses, that makes one question unavoidable: do we really know who we are dealing with? Used well, open-source intelligence can reveal hidden links, detect manipulated influence campaigns, and give early warning before a sponsorship, partnership or trade goes badly wrong. At Context First, this is the space we quietly serve in.

USE OF AI:

Estimated AI involvement in text and sentence structures: 10-15%.

The content was verified and edited by the author..